Three days ago I wrote about a series of strange and shocking events – murders, rumours of military coups and political conspiracies – that have made headlines in Turkey in the past three years. I listed these events as they came to my mind and as if they were unrelated. This impression of randomness could be seriously misleading, however.

In fact, reading Turkish newspapers and newly published books these days one enters the world of a multilayered thiller – Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose or Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code come to mind – in which every ominous event appears to be linked to the next. It is a world of secret patterns that are only revealed at the very end: a hidden plot that connects the murder of an Italian priest in a church in the Black Sea town of Trabzon in 2006, the attempted murder of a former PKK member in a mainly Kurdish city on the border with Iraq in 2005, the assassination of a high judge in a courtroom in the centre of Ankara in 2006 and the cold-blooded execution of Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink in the busy centre of modern Istanbul in 2007. Istanbul prosecutors currently seek to prove in an ongoing investigation that there is in fact a link between all these (and many more) crimes: a network of radical nationalist conspirators operating under the name Ergenekon. This in turn is linked to what Turks call derin devlet: the deep state.

What is Ergenekon? And what is derin devlet? Let us proceed cautiously from what is known before arriving at what is only suspected. In matters of conspiracies, it is best to treat carefully lest one gets lost in a fantasy world of multiple echoes and strange shadows.

First, devlet. When I arrived in Turkey a few years ago I was struck how often Turkish analysts would make a distinction between “the government” and “the state” in sentences such as “the state will not allow the government to do this” (for instance, use its sufficient parliamentary majority to elect a new president). I did not appreciate at the time the definition of devlet in the excellent book on Turkey (Crescent and Star, 2001) by former NYT correspondent Stephen Kinzer:

“The dictionary says it means “state”, but it also means something much uglier. Devlet is an omnipotent entity that stands above every citizen and every institution. Loyalty to it is held to be every Turk’s most fundamental obligation, and questioning it is considered treasonous. No one ever defines what devlet means; everyone is supposed to know. Its guardians are a self-perpetuating elite – the generals, police chiefs, prosecutors, judges, political bosses and press barons who decide what devlet demands of the citizenry. This elite has written many laws to help it do what it perceives as its duty, and when necessary it acts outside the law.” (p. 26)

The institutional foundation of devlet was (and is) the Turkish constitution of 1982. It was drafted under the supervision of the Turkish military that had taken power following a coup in 1980. The very first sentence of the preamble of the constitution spells out its underlying philosophy:

“In line with the concept of nationalism and the reforms and principles introduced by the founder of the Republic of Turkey, Atatürk, the immortal leader and the unrivalled hero, this Constitution, which affirms the eternal existence of the Turkish nation and motherland and the indivisible unity of the Turkish state …”

A few paragraphs further down the constitution spells out what this means:

“… no protection shall be accorded to an activity contrary to Turkish national interests, the principle of the indivisibility of the existence of Turkey with its state and territory, Turkish historical and moral values or the nationalism, principles, reforms and modernism of Atatürk …”

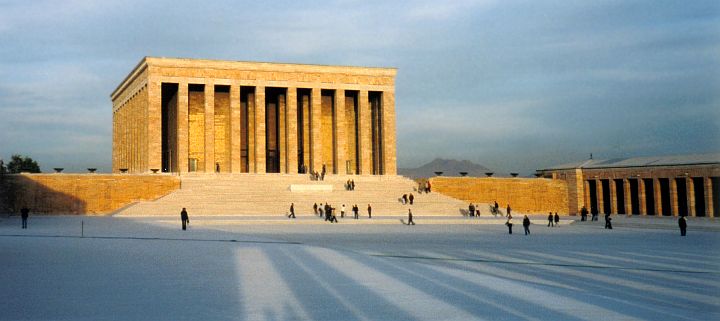

Ankara – Ataturk Mausoleum

There were many other provisions, in the constitution and in other laws, that buttressed the military’s vision of the national interest in post-coup Turkey: the military-controlled National Security Council, acting as a shadow government, the Higher Education Board controlling universities, laws on political parties (that made it easy to dissolve them) and on associations and foundations (to control these). The outside world was viewed as full of enemies, plotting to bring Turkey down and always looking for and finding domestic traitors to work with. As Stephen Kinzer wrote in 2001:

“Writers, journalists and politicians who critizice the status quo are packed off to prison for what they say and write. Calls for religious freedom are considered subversive attacks on the secular order. Expressions of ethnic or cultural identity are banned for fear that they will trigger separatist movements and ultimately rip the country apart.” (p.12)

This repression was not hidden, however: it was the public face of the state. In fact, the architects of this system and its guardians were unapologetic about the necessity to protect devlet by limiting individual rights and democracy.

What, by contrast, is derin devlet? It is those elements of the state which went even further than the repressive laws already put in place to fight the enemies of devlet with illegal methods.

Again, some things are known about how this worked. There were hundreds of mystery killings in South East Anatolia in particular during the 1990s. A particularly radical group such as (Turkish, no link to the Lebanese organisation) Hizbullah was one of the instruments used. This became clear when hideouts used by Hizbullah, containing bodies of people kidnapped and turtored, were found across Turkey. As Kinzer put it, “the true lesson was even more sinister. Hizbullah had not been a band of outlaws but an arm of the Turkish state. Security agencies in southeastern provinces had made common cause with these terrorists. … Hizbullah thugs were turned loose to kidnap and kill their enemies in the knowledge that the police would not investigate them.” (p. 100)

Then there was the famous car accident in Susurluk in 1996: the people who died in the car crash, sitting in the same Mercedes, included a top-ranking police commander, who had been involved in counter-guerilla operations against the PKK; Abdullah Catli, one of the most famous gangsters in Turkey; and a pro-government Kurdish clan chief and parliamentarian. Evidence emerged that linked Catli to numerous crimes since the 1970s, and that showed that he had in fact been recruited by government security agents as an assassin.

However, even such discoveries did not change the culture of impunity in the security apparatus. Politicians who dared to confront the security apparatus did not get far in the late 90s, and nor did prosecutors. A parliamentary investigation, which led to a thick report in 1997, was prevented to question some key suspects, who could have shed light on events and links between state institutions and the underworld. One of these suspects who were not investigated further was Veli Kucuk, who had been a high level military officer in South East Anatolia allegedly in charge of a special and secret military unit and who had last spoken to Catli before the accident. Kucuk is today once again a central figure in the current Ergenekon investigation and was arrested in January 2008.

In fact, much has changed in Turkey since 2001: torture is no longer tolerated, the formal role of the military has been reduced, the Penal code and laws on associations have been reformed. Many more changes are expected and required, should Turkey’s EU accession process continue successfully. There have also been many changes to the constitution, and following the election victory of the AKP in the summer of 2007 work started on drafting a new constitution – with a new preamble – to turn away from the tradition of devlet embodied in the 1982 document.

And yet other things have not changed. There are still those within the system who believe that there is an immutable concept of nationalism that has to be protected, if need be by illegal instruments, against its enemies. Fast forward to 2006, 2007 and 2008 and it becomes clear that the challenge posed by both the surviving authoritarian state tradition and the threat of deep state structures remains serious. This was never more clear than this week in March

To be continued …