One faithful reader tells me every time that my articles on this blog are too long. I tend to agree and apologise at the outset for this particular (long) entry.

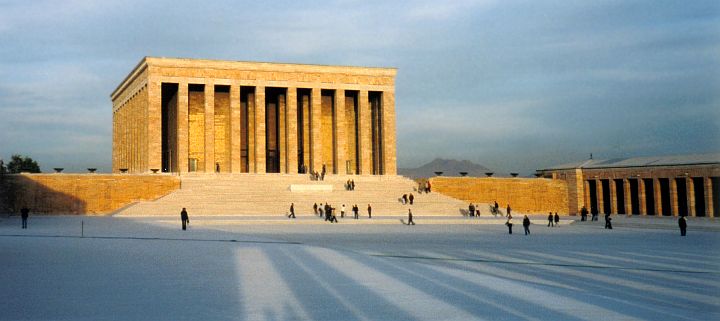

Outside the courtroom – Turkey’s trial of the Century @Jonathan Lewis

In April 2008 we put on our website the picture story The battle for Turkey’s Soul. Party closures, gangs and the state of democracy. There we told the story of the military coup dairies, found on the laptop of Admiral Ozden Ornek, the former Turkish navy commander, and published in the magazine Nokta on 29 March 2007:

“The diary entries contain detailed plans for a military coup, prepared jointly by the commanders of the army (Aytac Yalman), navy (Ornek himself), the air force (Ibrahim Firtina) and the gendarmerie (Sener Eruygur) in 2004.

According to the diary, it was only the opposition of the Chief of Staff at the time, Hilmi Ozkok, which prevented the coup plans from being put into action. The code name for the coup was “Blond Girl”. Later, these dairies suggest, Sener Eruygur had begun to plan another coup, code named “Moonlight.”

On 12 April, Nokta‘s offices were raided by the police in a 3-day operation at the request of the military prosecutor. Subsequently, the owner of the magazine decided to shut it down altogether.”

The authenticity of these coup diaries has since been confirmed during another court case against former Nokta editor-in-chief Alper Gormus. Tomorrow they are for the first time at the centre of the most complex court case in recent Turkish history: the so-called Ergenekon case.

A lot has happened since we wrote Turkey’s Dark Side in April 2008 and introduced the debate on what has since become known in the courtroom as the Ergenekon Terror Organisation (ETO).

A quick overview:

First, there was a wave of spectacular arrests in summer 2008. The most prominent arrest was of the former Commander of the Gendarmerie, retired General Sener Eruygur … the person singled out as the most eager general to carry out a coup in the Ornek diaries.

Then, in July 2008, the first Ergenekon Indictment was presented to the court. The document, 2,455 pages long, listed 86 people to be put on trial, among them 12 retired members of the Turkish Armed Forces. Veli Kucuk, allegedly both a leader within Ergenekon and one of the founders of the paramilitary gendarmerie unit JITEM (accused of involvement in extrajudicial executions for many years) was the most prominent.

Kucuk had also been a leading ultra-nationalist figure in the protests against Turkish Armenian journalist Hrant Dink, shortly before Dink’s assassination in early 2007. The main charge in the indictment was that Kucuk and other former military, together with police officers, nationalist journalists, academics and civil society figures, had formed an organised terror network to create chaos and thus trigger a military coup.

Weapons had been found, linking some of the accused directly to attacks against different institutions, including an attack on the highest administrative court (the Council of State) in 2006, which left one judge dead. Documents were found outlining the strategy and organisational structure of the Ergenekon network. Assassination plans were discovered, targetting politicians, liberal journalists as well as writer Orhan Pamuk.

The Ergenekon trial based on these charges began on 20th October last year.

“Ergenekon lie, American game” – Protests before trial starts October 2008 @ Jonathan Lewis

Since then there have been many more arrests. In another dramatic turn, a court decided in February 2009 that there was a strong enough case to merge the Ergenekon case with the case of the brutal murder of three Christian missionaries in Malatya (who were killed, after being tortured, in April 2006). In March 2009 death wells were opened in South East Anatolia and human remains exhumed (leading to further arrests of active military). Illegal weapons continue to be found in houses and hidden in places, marked on maps found among those arrested.

In March 2009, the second Ergenekon indictment, this time listing 56 suspects (among them 17 members of the Turkish Armed Forces, and for the first time 9 still active military) on almost 2,000 pages, was accepted by the 13th Serious Crimes Court in Istanbul. It is on the basis of this indictment that the next phase of the court case is set to begin tomorrow.

(A third Ergenekon indictment is expected to be submitted to the court any time soon).

It is certainly not surprising that this case has been controversial in Turkey almost from the beginning. Never before have so many prominent personalities, accused of being associated with the so-called deep state in Turkey, been put in court for such serious allegations. Never before have members of the Turkish Armed Forces (TAF) been put in a civilian court accused of planning to topple a civilian government.

He is not happy with the course of Turkish justice (Silivri, Ergenekon trial) @ Jonathan Lewis

And yet, while the judicial inquiry is continuing, extra-judicial challenges against the trial continue.

First there was the discovery, publicised in an article in June 2009 in the independent daily Taraf, of a plan by the Turkish military to help their accused colleagues by presenting the whole Ergenekon case as a campaign by followers of the (US-based) Sunni-preacher Fetullah Gulen; and by an AKP government bent on turning Turkey into Iran.

The document, called “Action Plan to Combat Reactionaryism” (sorry for this translation) was found in the office of lawyer Serdar Ozturk, who had been arrested as part of the Ergenekon investigation. It appears to be a product of the Support Section Directorate 3 of the Operations Department in the Office of the Turkish General Staff, drafted in April 2009! The text bears the signature of Naval Infantry Staff Senior Colonel Dursun Cicek. The text expresses profound dismay with the course of the Ergenekon investigation. It also suggests concrete ways to change the course of the case.

The Taraf article quotes directly from the text:

“Intensive activities are carried out by the religiously reactionary groups to erode the image of the official institutions of the state, particularly TAF (Turkish Armed Forces) as efforts are under way to blacken the names of retired and active military staff, who have made substantial contributions to TAF, by charging unfounded allegations against them as part of Ergenekon.”

“It will be ensured that any TAF staff members seized or agreeing to disclose would make statements in line with the themes determined by us and that such disclosure would have wide coverage in the press. “News articles will be fabricated that TAF staff members arrested under Ergenekon investigation are innocent and that they are slandered just because they effectively fight reactionary Islam. “News articles will be commissioned that no action being staged by PKK terrorist organization against any schools, classrooms and hostels in the Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia regions as well as in the north of Iraq, which are owned by Fetullah Gulen followers is a clear sign of a link between the two networks and also of an agreement between them.”

The plan calls for the following:

“to put an end to the hesitancy over this issue by revealing the internal face of the religiously reactionary elements and eradicate public support for such networks. To minimize the impact of the erosive campaigns staged under Ergenekon, to put an end to the negative propaganda carried out against TAF”.

“Information support activities will be executed to bring out to light the facts on the radical religious groups, particularly AKP government promoting the idea of establishing an Islamic state based on Islamic Law by overthrowing the secular and democratic order and various groups and Fetullah Güven group supporting it, to break the public support and put an end to their activities”.

Part of the plan covers “Black Propaganda Activities”:

“The theme, “Fettullah Gülen (FG) followers have gotten out of control, directly attacking TAF”, will be covered; in this scope, campaigns will be staged causing the citizens to comment: “This is beyond the limit! We are Muslim like them but FG followers are obviously making provocation to attack TAF”.

“Voice recordings which would be identified as having been broadcast by the religiously reactionary elements and cause listeners to find us justifiable will be arranged in order to create information pollution over the issue of voice recordings which have recently led to considerable repercussions.

“It shall be ensured that any staff members captured by fabricating cause publicly in connection with various information and documents would provide statements that they were FG followers and once such staff members were made public by the press, news articles shall be ordered about their morally negative aspects.

“It will be ensured that any objects associated with any elements (Jews, CIA, MOSSAD, Moon Sect, Khomeni, etc.) through which a link is intended to be established with FG followers, apart from any weapons and munitions there, would be on the same location by causing house raids to be staged on the basis of tips.

“It will be ensured that information and documents rekindling the Anti-Alavite feelings would be present in such houses as part of house raids.”

If you want to read the document in Turkish, go here. For the English version of the article go here. The debate about its authenticity (challenged by the military) will likely continue in the course of the ongoing Ergenenkon investigation.

If, that is, the investigation is allowed to continue normally. For there has been another major challenge recently.

Last week the Turkish press reported that some members of the Higher Council of Judges and Prosecutors in Ankara proposed to remove the current judges AND prosecutors from the ongoing Ergenekon trial. The annual decision on the rotation of judges and prosecutors has not been announced so far; it appears as if this issue has been holding up a decision.

That this is a serious matter is made clear by a recent precedent. In 2005 a prosecutor in Van, planning to investigate the background of a terror attack against a Kurdish bookshop in Semdinli committed by plain-cloth non-commissioned military officers, was dismissed from his post (and stripped of his right to work even as a lawyer) by a decision taken by the Higher Council of Judges and Prosecutors. The accusation against him was that he was “dishonouring the legal profession.”

The further evolution of the Semdinli case also highlights a challenge to the Ergenekon case. The perpetrators of the attack were first sentenced in a civilian court to 39 years in prison (no questions were asked there about who had ordered the attack). Then a higher court ruled that since this attack was carried out by the accused TAF members engaged in military duty the conviction did not stand. A new trial started, this time in a military court. The accused were set free pending a judgement. The case has not been concluded yet, despite overwhelming evidence (the accused had been captured on the spot after having thrown the grenade).

For the Ergenekon trial the major question has always been: could the same happen here?

This renders all the more significant a recent decision by the Turkish parliament, another unexpected turn in the dramatic struggles reshaping Turkey.

On 25 June the parliament changed the Criminal Procedure Code. It requires, from now on, that civilian courts try members of the armed forces accused of specific crimes, including threats to national security, constitutional violations, organising armed groups and attempting to topple the government. On 8 July this law was ratified by president Abdullah Gul.

But that is not the end of the story. Although the reform is a long demanded adjustment of Turkish legislation to norms prevalent in the rest of Europe, Turkey’s largest opposition party (CHP) has promised to challenge the changes before the Constitutional Court. Then again, CHP leader Deniz Baykal has long attacked the whole Ergenenon investigation as a political witch-hunt, defending general Eruygur as an honourable patriot.

Thus the battle over Ergenekon is not only taking place in a courtroom near Istanbul. It is part of a wider battle over the very soul of Turkish democracy … and over the question whether in the end it is the military or the elected government, and military courts or civilian courts, that have the ultimate say. The jury on this most basic question is, unfortunately, still out.