In recent years the government of Azerbaijan has been playing cat and mouse with the Council of Europe. In a recent newsletter (Hunger strike, European values and an Open Letter) and in an open letter to PACE members we suggested what might be done in response:

- Call on President Ilham Aliyev to give amnesty to Ilgar Mammadov, Anar Mammadli and the eight young activists on hunger strike before Azerbaijan assumes the chairmanship of the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers on 14 May 2014;

- Call on the Secretary General of the Council of Europe to travel to Azerbaijan urgently, and speak out strongly and forcefully on behalf of these and many other political prisoners;

- Support an initiative to appoint a new rapporteur on political prisoners to investigate the trend of imprisonment in Azerbaijan since the vote in January 2013.

Now at least one of these things appears to be happening: Mr. Jagland is going to Baku.

“The Secretary General of the Council of Europe is going to discuss the topic of political prisoners

The human rights situation in Azerbaijan will be one of the main topics on the agenda of the upcoming May 8th visit to Baku of the Secretary General of the Council of Europe Thorbjorn Jagland. It is learned from sources in Strasbourg that Yangland will also affect the situation with the detention of IPD director Leyla Yunus and her husband Arif Yunusov and pressure on them. Also touched upon will be the political prisoners and the need to address this problem due to commence in May of the chairmanship of Azerbaijan in the Committee of Ministers. “

Of course, it remains to be seen what will come out of this visit. However, the mere fact of Mr. Jagland going to Baku should raise expectations. Mr. Jagland has a legacy to defend. He has been secretary general since September 2009. He is also running for reelection for a second term in a few weeks’ time.

There is little that a secretary general can do directly to prevent member states of the Council of Europe from violating human rights. However, one thing a secretary general must do is speak out openly about systemic violations of human rights in a member state. Today the credibility of the whole institution is at stake as a result of Azerbaijan’s years of abuse of its principles. It is thus crucial that Mr. Jagland achieves something on his forthcoming visit to Baku.

Developments in recent days have added to this urgency. There has been further harassment of distinguished Azerbaijani human rights defenders – and this at the very moment when Azerbaijan presented its program for the chairmanship of the Council of Europe (see below). In the next six months the Azerbaijani government proposes to host events to discuss the role of human rights education, the work of judges in defending human rights, the future of youth … while at the same time it hosts show trials against human rights defenders, journalists and youth activists. Can any of these events be taken seriously while Azerbaijan engages in this cynical behaviour?

Recent days saw: the arrest of journalist Rauf Mirkadirov. The arrest of Leyla Yunus and her husband Arif Yunus. The persecution of critical thinkers on espionage charges. With rare exceptions, such as the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, Nils Muižnieks, most European policy makers have remained silent. (See also this statement by Catherine Ashton and Stefan Füle).

In contrast, the NIDA youth activists, on hunger strike for two weeks, made a remarkable statement at the close of their trial in Baku last week. Their moral courage in the face of injustice puts to shame the current ineffective human rights protection machinery in Strasbourg. It also casts a shadow over the very notion of Azerbaijan as a chairman of the Council of Europe. In their final speech in court, after 15 days of hunger strike, the NIDA activists evoked the great dissidents of the Soviet period to explain their motivation:

“Solschenitzyn in his “Live Not By Lies” wrote about despotic regimes’ dependence on everyone’s participation in lies. He wrote that the simplest and most accessible key to our self-neglected liberation lies right here: in personal non-participation in lies. This is what Nida does.

Nida civil movement tried to resist and prevent a complete victory of this government’s policy. Our and other members’ ongoing arrests, openly demonstrated anger and irritation prove that we are on the right track to hamper this policy.”

They also directly addressed the judges and prosecutors:

“… in order to calm your conscience, to give you comfort, we are letting you know that the years that are being taken from our lives with your sentence are not going to waste. It is a capital investment for the freedom of Azerbaijan. So, even though you may be an anti-hero, you are also doing some things for this country.”

This is a speech and political activism in the tradition of non-violent resistance to authoritarianism of Liu Xiaobo. In the tradition of defending human rights as done by Andrei Sacharov. In the tradition of the 1977 Nobel Peace Prize given to Amnesty International.

Andrei Sacharov – Nobel Prize Winning former political prisoner

This makes it all the more poignant that the recent increase in repression and in the number of arrests of human rights defenders are happening at a time when the secretary general of the Council of Europe is also the Chair of the Nobel Peace Prize Committee.

We hope that Mr. Jagland will achieve something next week.

We hope that the game of cat and mouse that Azerbaijan has been playing with political prisoners will come to an end.

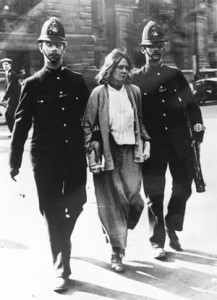

100 years ago: arrests could not break them: Suffragette in London

East European dissidents are not the only proud tradition which events in Baku bring to mind today.

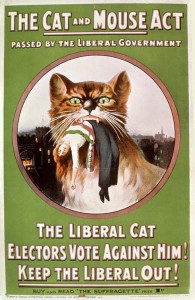

One hundred years ago, in 1913, the British government passed what became known as the Cat and Mouse Act to break the will of a group of courageous women – the suffragettes – fighting for the right to vote. The law was called the Prisoners, Temporary Discharge for Health Act:

“The Liberal government of Asquith had been highly embarrassed by the hunger strike tactic of the Suffragettes. Many of the more famous Suffragettes were from middle class backgrounds and were educated. When some suffragettes were arrested they would go on hunger strike. This was a deliberate policy to bring attention to their cause and also to embarrass the government.To counter this, the government resorted to force-feeding those women on hunger-strike – an act usually reserved for those held in what were then called lunatic asylums. This simple act greatly embarrassed the government.

To get around this, the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ was introduced. The logic behind this was simple: a Suffragette would be arrested; she would go on hunger strike; the authorities would wait until she was too weak (through lack of food) to do any harm if in public. She would then be released ‘on licence’. Once out of prison, it was assumed that the former prisoner would start to eat once again and re-gain her strength over a period of time. If she committed an offence while out on licence, she would be immediately re-arrested and returned to prison. Here, it was assumed that she would then go back on hunger strike … The nickname of the act came about because of a cat’s habit of playing with its prey (a mouse) before finishing it off.”

The suffragettes were fighting for a then radical idea – women having the same political rights as men – just as NIDA activists are defending the radical idea that the European Convention on Human Rights and its provisions also apply to Azerbaijan. The goal of the British government at the time was to break their will, without too much embarrassment, by playing cat and mouse. The same is happening in Baku today.

In the end, history was not on the side of the British government . Today, history is not on the side of the regime in Baku. Mr. Jagland might evoke the long tradition of political prisoners his Nobel Peace Prize Committee has honoured. He might also recall the history of the Suffragettes. And tell president Ilham Aliyev that he is on the wrong side of history. It might not work this time. But at the very least, the Council of Europe should not be on the wrong side of history too.

Suffragette poster – UK early 20th century

PS: Is it possible for a dictatorship, imprisoning its own human rights defenders, to plan a full Council of Europe chairmanship programme, without ever drawing attention to its own abysmal human rights record? And if it is, what does this tell us about the state of the institution?

Find below the draft program of the Azerbaijani Council of Europe chairmanship. Will any of the participants from across Europe even blush when they are being welcomed by the regime of Aliyev to discuss the following?

20 to 21 May: Meeting of coordinators of the Council of Europe Charter of Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights

22 to 23 May: Meetings of the PACE Bureau and Standing Committee

1 to 30 June: Conference on Public service delivery in the context of human rights and good governance

17 June: Meeting of the CLRAE Bureau

18 to 20 June: Baku Conference of European Ombudspersons

20 to 21 June: Conference on the new “Council of Europe Platform on the Impact of Digitisation on Culture”

30 June to 1 July: High-level conference on combating corruption

3 to 4 July: Plenary meeting for the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice

1 to 2 September: Annual exchange meeting on religious dimension of intercultural dialogue

1 to 30 September: Platform meeting on youth foundation and financing structures

10 to 11 September: Seminar to review the Council of Europe Social Cohesion Strategy and Action Plan

18 to 21 September: High-level conference on the Council of Europe Neighbourhood Policy

1 to 5 October: Event within the “No hate speech movement” of the Council of Europe

6 to 9 October: Celebration of European Heritage Days 2014

10 to 11 October: High-level conference on the role of national judges on enhancing domestic application of the ECHR

20 to 26 October: The 4th regional ministerial meeting on the implementation of the European Higher Education Area

28 to 30 October: UN Global Forum on Youth

30 to 31 October: Cultural Routes Advisory Forum Policy

Recommended reading:

Solschenitsyn – Live not by Lies (1974)

So in our timidity, let each of us make a choice: Whether consciously, to remain a servant of falsehood—of course, it is not out of inclination, but to feed one’s family, that one raises his children in the spirit of lies—or to shrug off the lies and become an honest man worthy of respect both by one’s children and contemporaries.

And from that day onward he:

- Will not henceforth write, sign, or print in any way a single phrase which in his opinion distorts the truth.

- Will utter such a phrase neither in private conversation not in the presence of many people, neither on his own behalf not at the prompting of someone else, either in the role of agitator, teacher, educator, not in a theatrical role.

- Will not depict, foster or broadcast a single idea which he can only see is false or a distortion of the truth whether it be in painting, sculpture, photography, technical science, or music.

- Will not cite out of context, either orally or written, a single quotation so as to please someone, to feather his own nest, to achieve success in his work, if he does not share completely the idea which is quoted, or if it does not accurately reflect the matter at issue.

- Will not allow himself to be compelled to attend demonstrations or meetings if they are contrary to his desire or will, will neither take into hand not raise into the air a poster or slogan which he does not completely accept.

- Will not raise his hand to vote for a proposal with which he does not sincerely sympathize, will vote neither openly nor secretly for a person whom he considers unworthy or of doubtful abilities.

- Will not allow himself to be dragged to a meeting where there can be expected a forced or distorted discussion of a question. Will immediately talk out of a meeting, session, lecture, performance or film showing if he hears a speaker tell lies, or purvey ideological nonsense or shameless propaganda.

- Will not subscribe to or buy a newspaper or magazine in which information is distorted and primary facts are concealed. Of course we have not listed all of the possible and necessary deviations from falsehood. But a person who purifies himself will easily distinguish other instances with his purified outlook.

No, it will not be the same for everybody at first. Some, at first, will lose their jobs. For young people who want to live with truth, this will, in the beginning, complicate their young lives very much, because the required recitations are stuffed with lies, and it is necessary to make a choice.

But there are no loopholes for anybody who wants to be honest. On any given day any one of us will be confronted with at least one of the above-mentioned choices even in the most secure of the technical sciences. Either truth or falsehood: Toward spiritual independence or toward spiritual servitude.

The Palace of Europe in Strasbourg

The Palace of Europe in Strasbourg Council of Europe

Council of Europe