NERP, not NERD

“NERP” sounds like “NERD”: may this contrast – or this photo – help you remember this particular acronym. NERP stands for National Economic Reform Programme. Last year the European Commission asked all Western Balkan governments to produce one NERP a year. (Proposed on page 8 here). The 2015 Kosovo NERP report is in fact different from the nerdish, impenetrable language of many economic analyses published on the Balkans in recent years. It deserves to be read widely.

The 2015 Kosovo NERP is 129 pages. Probably few people intend to read it in full. This would be a pity, as it provides a good foundation for a serious debate. In fact, the report hides its radical implications with its first sentence:

“Kosovo has been one of the very few countries in Europe and the region of South Eastern Europe that had positive growth rates in every single year in the period since the 2008 outbreak of the global financial crisis.”

This is not wrong, but it is misleading, as the analysis itself quickly makes clear. While everyone knows that Kosovo is poor, exports little, attracts little foreign investment and creates few jobs the NERP tell a far more disturbing story.

Kosovo’s problem in six figures

The 2015 Kosovo NERP contains many numbers, but some that are particularly telling. Between them, these six numbers tell you (almost) everything you need to know about Kosovo’s economy.

(1) EXPORTS

305 million Euros – the total value of goods Kosovo exported in 2013

An annual export number of 305 million Euro is abysmally low. For comparison: Estonia exported goods worth 12.3 billion Euros in 2013. Estonia has a much smaller population than Kosovo.[1] It is also worrying that in 2013 two thirds of these exports were “base metal and mineral products.” This means there are barely 100 million Euro of other exports (food, vegetables, plastics) that produce added value. Kosovo extracts minerals from the earth and sells them – but it produces very little.

(2) IMPORTS

2.3 billion Euros – the total value of goods Kosovo imported in 2013

This is very high compared to Kosovo’s exports. So how is the gap financed? How do Kosovo importers obtain these 2.3 billion Euros to import goods? One must assume that they obtain much of this from Kosovars who earn this money abroad.

(3) REVENUES

The level of imports is directly linked to the third number:

1.3 billion Euros – total revenues (income) of the Kosovo government in 2013. No less than 871 million of this comes from border taxes on imports

This means that the state – 70 percent of its total revenues – depend on imports taxed at the border (customs, excises, and VAT on imported goods).

To maintain the current level of public spending, imports need to remain at least as high as they are now. If less money is transferred to Kosovo by Kosovars abroad, for whatever reason, government revenues will contract quickly. Even if government revenues and spending are in balance (with a low government deficit), and even if the debt of Kosovo’s government is relatively low as a share of GDP, the structure of public finances is very fragile.

(4) EMPLOYMENT

The fact that Kosovo produces few goods, which people outside of Kosovo (low exports) or inside Kosovo want to buy translates into tragically low numbers of jobs. Here is the fourth number:

220,000 people – registered as employed in 2013

There is sometimes confusion in public debates about “employment.” They frequently get mixed up with debates on the distinction between the official and unofficial (grey) economy. In fact it is simple: there are two ways to measure how many people work, which always give different results as the meaning of “employed” is different in each case.

The first way is to look at registered jobs. These are jobs which are known to public authorities and which are taxed. The second way is to do a representative survey of the labour force, based on samples. In the Kosovo Labour Force Survey (LFS), or any other such survey elsewhere, this is how “employment” is defined:

“People aged 15-64 years who during the reference week performed some work for wage or salary, or profit or family gain, in cash or in kind or were temporarily absent from their jobs.” (LFS 2013, page 7)

This includes anyone in the family of that age who works “for family gain” on their small plot of land, milks the cow, looks after vegetables during the reference week, even if nothing is then sold for cash. In a country with a lot of subsistence farming this number is always much higher than registered employment. In Kosovo in 2013 this number was 338,000 people.

These two figures of employment allow us to estimate the size of the Kosovo private sector. There are 77,000 jobs in the public sector (paid by the state). This leaves 143,000 jobs in the registered private sector. Then there are another 118,000 people “employed” (LFS) without being registered.

Even added together, this number is shockingly low. Kosovo’s resident population of 1.8 million people divides into some 297,000 households (the average household has 6 members, still the largest households in Europe today). Even including all employment (per LFS definition), and all subsistence family farming on tiny plots, this yields barely one “employed” per household.

No wonder only slightly more than one in ten women of working age in Kosovo are “employed” (even by the LFS definition). No wonder Kosovo households have few savings: every employed person has to support five other people (dependents).

(5) FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

All of this raises the key development question: will Kosovo businesses – existing or new ones – develop more competitive products for new markets in the coming years?

Gaining market share in export markets requires competing successfully against businesses from other countries, from the EU, the Balkans, Turkey. This requires investment, such as new machinery. New or expanding businesses in Kosovo can be either foreign (through FDI) or domestic.

Here is the fifth number:

241 million Euros – Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in 2014

This is very low by any standards: it means that very few foreign companies show any interest in using Kosovo as a base for their production and transfer their machinery and know-how here.[2] And, as the NERP notes, FDI has been decreasing in recent years:

“Since 2007, net FDI inflows have been volatile and with an overall negative trend … the sectorial composition of FDI has shifted towards real estate and construction between 2009 and 2013.”

What the NERP does not give us is the value of all cumulative FDI (the FDI stock) in Kosovo. For comparison: in Estonia in 2014 this FDI stock is around 15.9 billion Euro. Kosovo’s total GDP is only 5.3 billion Euro.

(6) COST OF CREDIT

The sixth number tells us what opportunities existing Kosovo entrepreneurs have if they want to develop:

10 percent – the annual interest rate on loans in November 2014 (in November 2013 it was 12 percent)

This is very high. Again, look at Estonia (European Central Bank data): loans to non-financial corporations – depending on specific conditions – carry around 3 percent annual interest at the end of 2014.

What do these six numbers tell us about the Kosovo economy?

- Export of goods is very low; given current trends of declining FDI and high costs of borrowing for businesses in Kosovo this is unlikely to change anytime soon. The NERP projects a best case scenario in which the export of goods increases from 305 million Euro to 441 million Euro by 2017.

- There is little structural change in the Kosovo economy compared to one decade ago. The GDP growth that has happened has been the result of households spending money (consumption) based on transfers from abroad and increases in public sector salaries (funded largely through border taxes on imports of goods, which are bought largely with money transferred from abroad).

- The employment rate will remain very low in the foreseeable future. If new jobs are created in the next years in the private sector one might expect some subsistence farmers to turn away from non-cash production to other – regular – employment. In order to really increase employment rates and create new jobs Kosovo would need levels of investment and export growth that are simply not on the horizon for many years to come.

- This makes public policy in many areas hard to formulate. Take the issue of skills needed for the labour market. What jobs does today’s generation of young Kosovars need to be prepared to take? What skills will they need? Unless there is a realistic job of more jobs in the foreseeable future this question is impossible to answer.

All of this is well set out in the NERP. At the same time it also underlines the main gap in the NERP analysis: the absence of any analysis of the economic impact of current and future migration flows.

While the word remittances appears many times, “migration” does not appear anywhere in the text. At the same time everything described in the NERP – the huge trade deficit, a public sector funded to 70 percent by border taxes, recent GDP growth – is the direct consequence of the migration that took place many years ago. There is no discussion of what policies – education, social and foreign policy – might make regular migration from Kosovo to the EU possible. This created the lifeline of remittances that keeps Kosovo households – and the public sector – afloat today. This is the lifeline that the EU has tried to cut since 1999, making it increasingly difficult for Kosovars to migrate to work.

This is a dangerous omission. But it is not surprising. In the current Kosovo government programme “migration” is discussed only under the heading “diaspora”, as a foreign, not an economic development issue.

“Promotion of Kosovo Diaspora and realization of objectives arising from Strategy on Diaspora and Migration 2013-2018, which is related to the preservation of national and cultural identity of Diaspora, to creation of conditions for the participation of Diaspora in the political and social life and their representation in decision-making institutions of the country, integrating them in countries where they live, as well as involvement of Diaspora in socioeconomic development of the country.“

Kosovo Government Programme 2015-2018

This half sentence is not followed by any concrete policy measure.

The pressure on Kosovars to look (legally or illegally) for work and income elsewhere will grow ever stronger in coming years. How strong this pressure is already has recently become obvious to policy makers in the EU and in Kosovo.

ESI argues that the European Union, instead of simply opposing this pressure, should try to channel it in mutually beneficial ways. Illegal and irregular migration needs to be stopped, but opportunities for regular, or circular work migration need to be opened. This will also require a major effort on the part of Kosovo authorities in many policy fields, starting in education policy.

The first paragraph of the NERP euphemistically refers to “the country’s rather specific development model.” What is today specific about this model is that it is not about development in Kosovo at all. As the NERP notes, Kosovo experienced growth:

“… based on strong remittances and FDI inflows from diaspora that boost domestic demand through household consumption and investments channelled primarily into the non-tradable sector, such as real estate and services.”

This is growth dependent on wage earners in Germany, Switzerland or Austria with links to family members resident in Kosovo. The NERP refers to some risks:

“The existing growth model of the country based on large financial inflows is associated with significant risks. On the short run, the main risk factor would be a sudden fall of these inflows – caused by unfavourable economic developments in countries with the largest Kosovo diaspora – and its negative consequences for growth, public finances, and external and financial sector stability.”

But then it falls silent. It does not discuss the role of EU policies that try to prevent further migration.

Young Europeans – but not part of Europe today

The NERP is an interesting document. More will be said on this blog later on its recommendations to increase exports. But the main value of the NERP lies in showing what many prefer to forget: while migration alone is no development policy, without migration Kosovo has no medium term economic future. Simply put:

The Kosovo “growth model”

| Workers abroad, with family in Kosovo | SEND | Money that fuels local consumption. This funds imports. Taxation of these imports is the core of public revenues |

EU member state policy

STOP Kosovars moving abroad to work illegally

CLOSE most possibilities to move to work abroad legally

Greatest risk to Kosovo “growth model”

Current EU member state policy succeeding.

In order to develop a credible migration policy, the vital importance of migration needs to be acknowledged first, including in the NERP. It is never too late.

Looking for workers with specific skills: www.make-it-in-germany.com

Further reading:

[1] Estonia: 1.3 million. Kosovo 1.8 million.

[2] The definition of FDI according to the World Bank: “Foreign direct investment are the net inflows of investment to acquire a lasting management interest (10 percent or more of voting stock) in an enterprise operating in an economy other than that of the investor.”

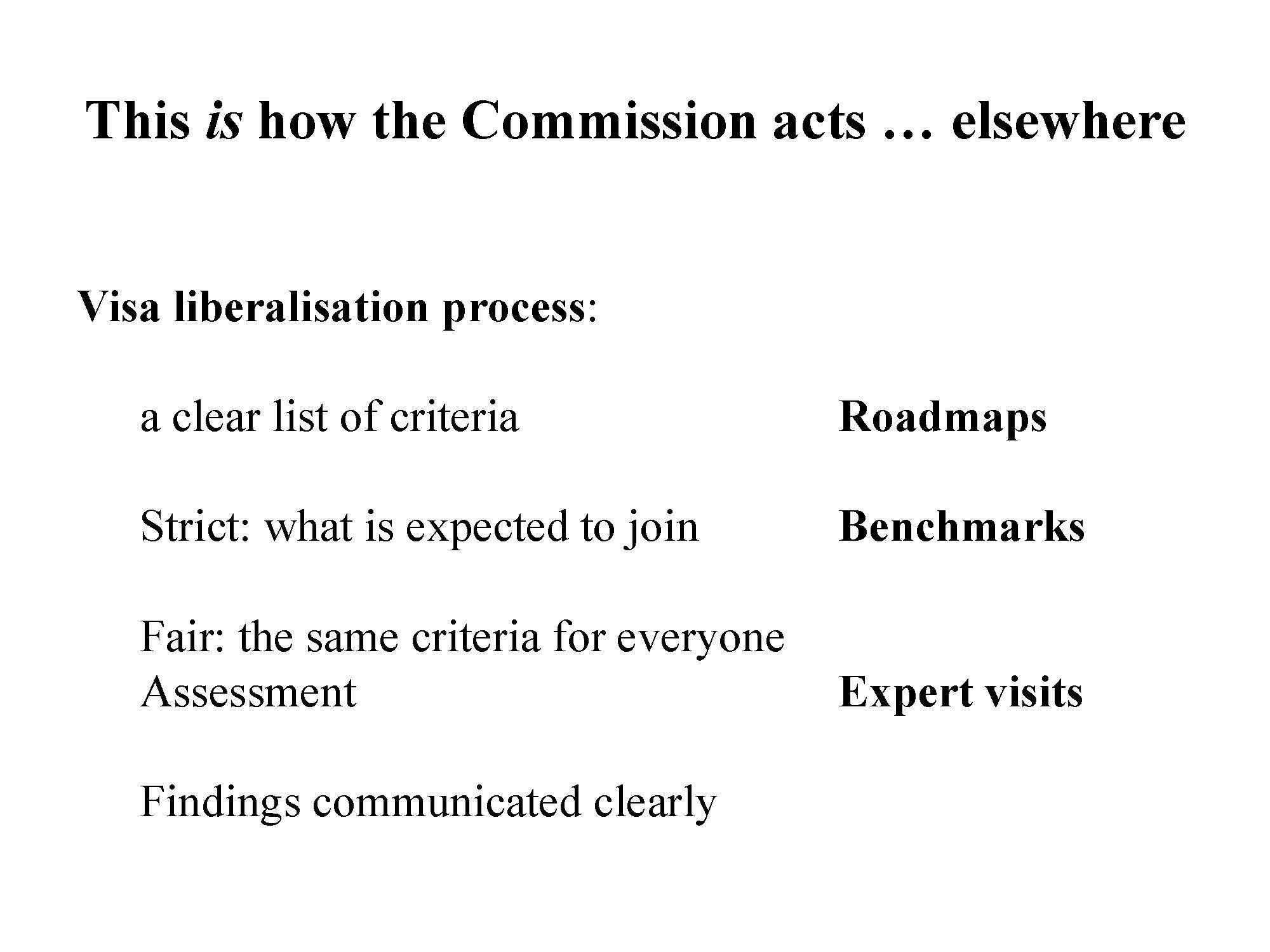

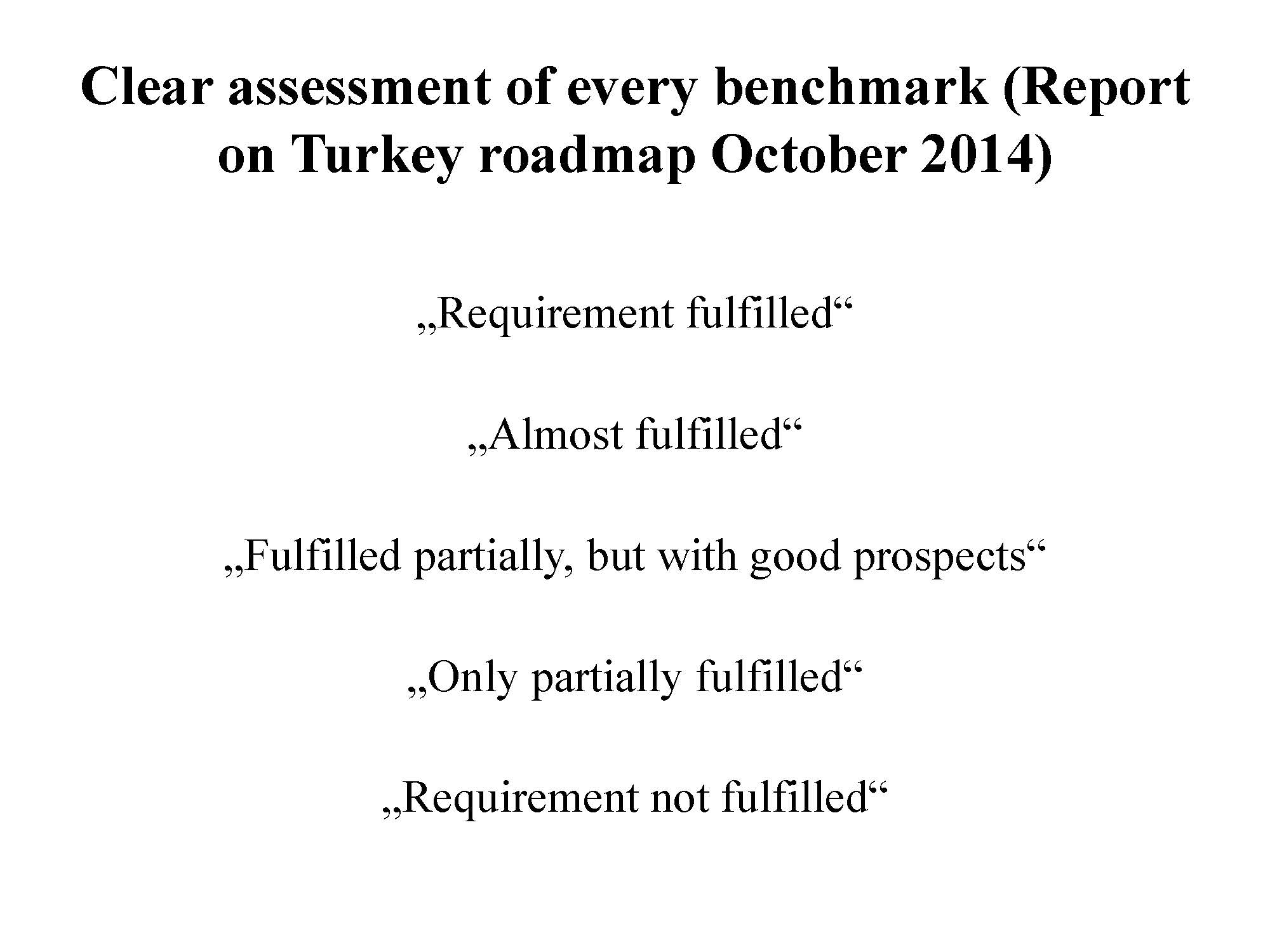

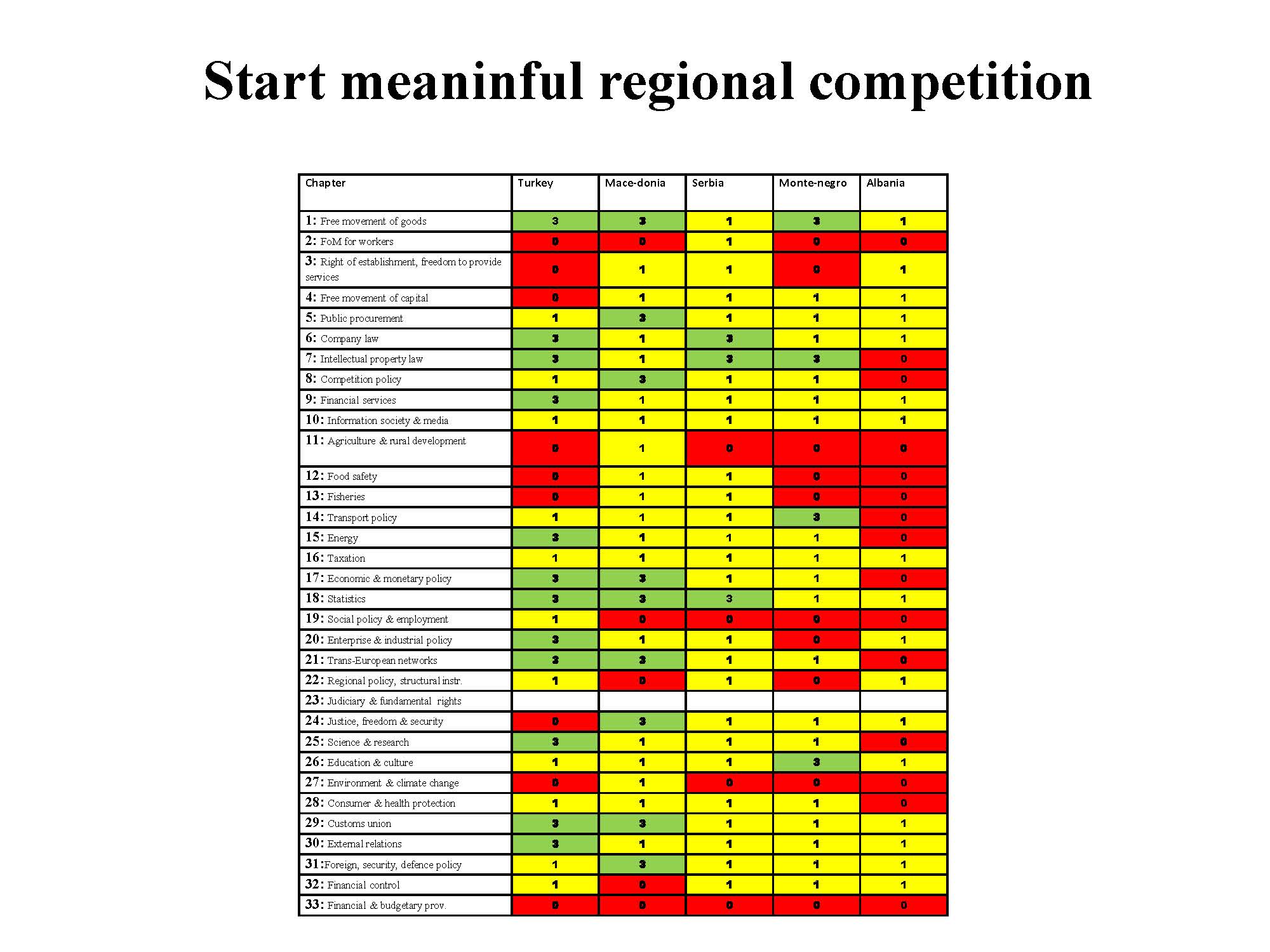

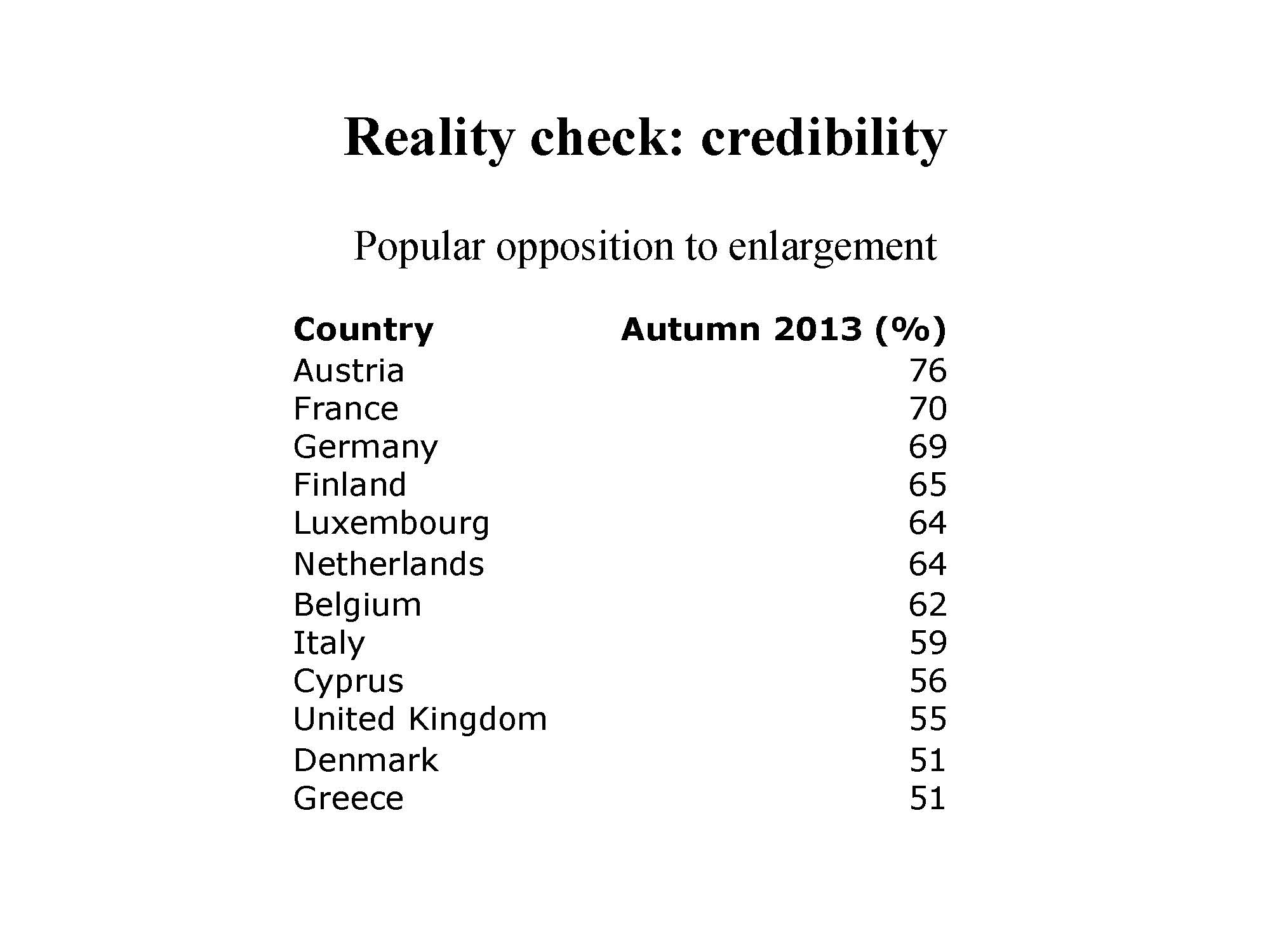

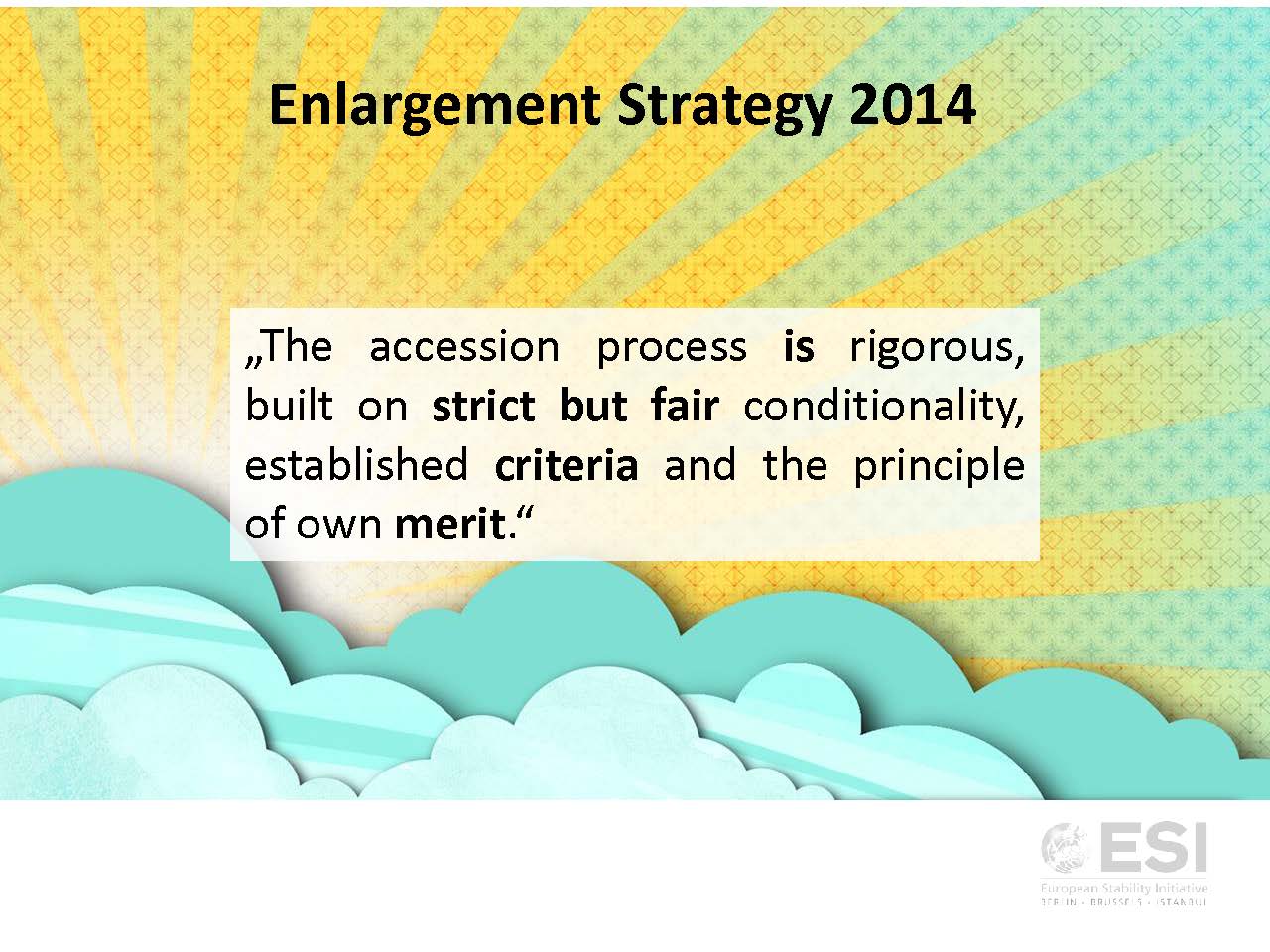

This is a standard claim, made by EU member states and by the European Commission. On 7 June 2014 the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, made a video podcast on Western Balkan enlargement in which she asserted: “There are very clear criteria for the steps needed to move closer to the EU. In the end it is up to each country whether they pass through this process rapidly or not.” The message: “the process is fair. It depends on merit. It depends on you.”

This is a standard claim, made by EU member states and by the European Commission. On 7 June 2014 the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, made a video podcast on Western Balkan enlargement in which she asserted: “There are very clear criteria for the steps needed to move closer to the EU. In the end it is up to each country whether they pass through this process rapidly or not.” The message: “the process is fair. It depends on merit. It depends on you.”