Lebanon got under my skin.

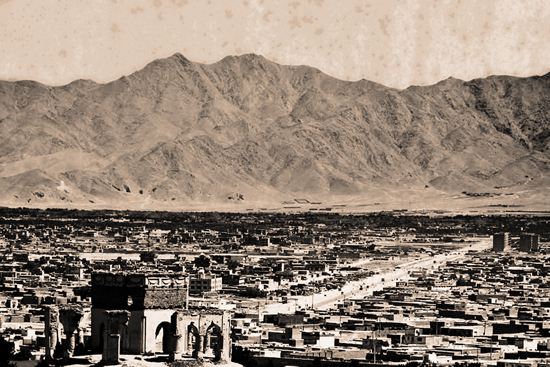

It was not the beauty of the place. Beirut is a city with little to discover for the classical tourist. One can walk along the Corniche – the boulevard along the Mediterranean coast. One can spend time getting lost in the shopping streets of Muslim West Beirut. One can eat in good French restaurants in the Christian quarter. On Saturday evening all the outdoor tables of the many restaurants in the rebuilt downtown are full with people, many smoking water pipes. All of this is nice, the weather in October is glorious, but the sights hardly compare with Istanbul or Thessaloniki: not the walks along the water, not the shops, not even the restaurants and cafes.

What transforms this city into something remarkable is not what one can see but the stories that cling to every building: it is discovering the downtown’s pre-war history, its war-time fate and the remarkable story of its reconstruction after 1990 (which is still ongoing), that turns sitting here into an exercise of rubbing Aladin’s lamp. Ghosts quickly appear, and take one on trips to the past and future.

First one finds oneself in the middle of a pleasing yet “sterile urban ideal of cobble-stoned streets, art galleries and boutiques” (Nicholas Blanford): the present. Then one sees oneself sitting on top of an archeological goldmine, with Roman roads, Greek mosaics, Phoenician burial chambers: the distant past. The next image is of this very same place looking like “a wasteland of shell-scarred ruins and overgrown streets, inhabited by families of destitute squatters and packs of prowling wild dogs”: the downtown two decades ago. Then “countless bullet holes pitted the sandstone facades of Ottoman-era houses lining streets named after First World War generals such as Foch, Weygand and Allenby” (Nicholas Blanford in his gripping “Killing Mr. Lebanon”). I look up and see that the elegant shopping street where I sit is still named after Allenby today.

On Saturday I drive to Byblos. This is one of the oldest towns in the world, on the coast north of Beirut. It was one of the obvious tourist attractions when a 2-day visit to Lebanon was still part of most package tours to the Middle East. Tourists would be shown the remains of a crusader castle and a 12th century church, some Ottoman buildings, and a little harbor going back to Phoenician times. A picturesque and interesting site, definitely worth an excursion but hardly warranting a special trip. Today there are very few tourists, however. I learn in Byblos that most EU embassies have put out a travel warning for Lebanon, so tour operators coming to Syria do not dare to come here at the moment.

What fascinates me more than the old remains is the drive from Beirut to Byblos (Jbeil in Arabic): the chaotic and dense construction along the coast, the obvious lack of urban planning, coinciding with the construction of shopping centres, casinos and nightclubs: a “glittering and shallow facade of ersatz Westernization for rich Arab tourists”, as one author unkindly calls it. The Beirut metropolitan area does not end north or south of the city itself. Kosovo is one of the most densely populated countries in Europe, with some 2 million people living on 10,000 km2. However, in Lebanon there are 4 million people living in a territory of the same size as Kosovo. This is a very crowded place indeed.

The area north of Beirut is largely populated by Christians. Lebanon’s current president (who is always a Maronite Christian) comes from here (the Maronites are the largest Christian group). Here, as in East Beirut, one can see evidence of Christian life everywhere: pictures of the Virgin, statutes of saints, signs pointing to educational establishments run by religious orders.

Lebanon is not only crowded; its population is also – proverbially – extremely diverse. It was the strong presence of the Maronites in the region of Mount Lebanon which led the French to create Lebanon as a separate country, severing it from Syria when both were a French protectorate. This explains one cause of Lebanon’s recent turmoil: a Syrian reluctance to accept Lebanon as a fully sovereign neighbour. Damascus is only some 30 kilometers away from the Lebanese border, and friends tell me that it takes less than 2 hours to drive there from Beirut.

Lebanon’s diversity has been a source of tensions throughout its modern history. Who should be in charge? How is power to be divided between different sects, Christians and Muslims, Sunnis and Shiites, Druze, Armenians, smaller Arab Christians groups and the very large number of Palestinian refugees? The formula found to share power was “confessionalism”, based on a very rough idea how many people of different faiths lived in the country. And since demographic balances change over time, it was decided early on to stop counting the ethnic make-up: ignorance was to be a solution where too much knowledge was dangerous.

In her book Bring down the Walls Carole H. Dagher describes the demographic evolution. The last official census was undertaken in 1932: then there were 32,4 percent Christian Maronites, 9.8 percent Greek Orthodox, 5.9 percent Greek Catholics as well as 22.4 percent Sunnis, 19.6 percent Shiites and 6.5 percent Druze (plus other smaller groups).

By 1990 the total number of Christians had fallen to 43 percent, plus another 29 percent Shiites, 24 percent Sunnis and 4 percent Druze. These figures do not include some three to four hundred thousand (mostly Muslim) Palestinian refugees, nor a large number of guest workers from Syria. It is due to this “fragile balance” that even the descendants of Palestinian refugees who arrived in 1948 have not been given citizenship or other basic rights (such as owning property) in Lebanon. This was an obvious second major cause of instability in recent decades: the uncertain relation between Lebanese society and these refugees, and the direct link this created between Lebanese politics and the wider Arab-Israeli conflict (triggering a number of Israeli interventions).

And yet, comparing population figures from the beginning and the end of the 20th century, one remarkable fact stands out: how little has changed.

By the standards of the early 20th century Beirut was a normal Ottoman town: a city with an ethnic variety similar to Istanbul, Izmir, Jerusalem or Thessaloniki. By today’s standards Beirut boasts an almost uniquely mixed Christian-Muslim population. In most other places, including Mediterranean Europe, such diversity was destroyed in the 20th century. In Beirut it survived.

Visiting this city today is thus to travel back in time to the communal organisation of Ottoman times. As Charles Winslow wrote: “People in the Middle East must not only learn to live with differences but also must institutionalise the means of doing so … the individual needs security at the communal level, something parallel to what the old Ottoman millet system used to provide.” Sectarianism remains very much alive today, even though the Taif accord, which ended the war in 1990, had called for the “phased abolition of political sectarianism.”

Walking through Beirut I begun to wonder: was this what Istanbul “felt” like one century ago, when it was still a city with a large Christian population? When villages along the Bosporus were populated by Greeks and Armenians and when today’s Bosphorus university was run by American protestants? When the legacies of the millet system were still visible?

It is difficult to feel romantic about Beirut’s diversity, even if it is impossible not to be fascinated by it. Everywhere there are reminders of a recent history of inter-religious conflict as much as of millenia of coexistence. Opening the English or French daily papers, one reads about continuing tensions which confound all easy categorisation: there is a history of Muslims fighting Muslims, of Christian militias fighting other Christians. The crisis of this moment is one pitting Salafist Sunnis near the Northern city of Tripoli against other, more moderate, Sunnis and the government (as one recent Carnegie Paper on “Lebanon’s Sunni Islamists” describes well). At the same time, throughout most recent conflicts, the large Armenian community in East Beirut also managed to stay neutral in the confessional battles of recent decades.

[As elsewhere, I wonder if Samuel Huntington has ever actually set foot in Lebanon: he could not have possibly have come up with his theory of the clash of civilisations in light of this particular complex story]

In fact, visiting today’s Lebanon is a bit like visiting a modern-day Al Andalus … only without the romanticism that comes with the distance of time. A place where the meeting and mingling of cultures and religions can be observed without any certainty about the next chapter in an open-ended story of coping with diversity. And as in the case of medieval Spain there is a sense that the fate of multi-confessional Lebanon, like that of multi-confessional Bosnia, matters in a wider sense.

Carole Dagher concludes her book Bring Down the Walls with a reference to the “mission” of Lebanon:

“Its challenge illustrates somehow the challenge of the entire region. The failure of the Lebanese would mean the failure of a meaningful experiment in the Arab world to manage religious pluralism and cultural diversity, and to institutionalize freedom, equality, respect and participation for all. It would deprive the Arab world of a model it could relate to, reminiscent of its lost Andalus.”

The history of medieval Spain was a history as much of interaction as of conflict. There were local struggles, manipulated and even instigated by outsiders; crusading Christians in the North and fanatical North African rulers in the South played their part in the eventual destruction of a unique culture. But today Andalus is a myth, no less than its hero, the mercenary El Cid.

Multiethnic Beirut is a reality; the fate and future of this modern millet system a matter of war and peace. Beirut is Mark Mazower’s Thessaloniki without being a city of ghosts: a place where different confessions continue to live together as they did a century ago. It is a mirror of a universal promise, and having looked into it, it becomes hard to tear oneself away.

It is on my way to the airport that I finish another little book, recommended by a friend: Mai Ghoussoub’s Leaving Beirut. If there is one book on Lebanon that I have come across these days and that I would recommend to you to read it is this one: an ingenious personal reflection by a Lebanese writer, artist and activist on the urge for revenge after horrendous crimes, on slippery notions such as honour and treason in times of conflict. It is a very rich book and I will return to it later, but let me conclude my description of what I saw in the mirror of Beirut with Ghassoub’s case study of Lebanese reconciliation:

“In Lebanon, in 1994, the victims of a massacre in the Chouf area were invited to participate in a three-day conference on Acknowledgement, Forgiveness and Reconciliation – Alternative approaches to conflict resolution in Lebanon. The village concerned, Maasir al-Chouf, a Christian enclave in a Druze-dominated area, had lived in peace for the major part of the civil war. So much so that a few days before the massacre, a number of French journalists, invited to visit this haven of civil coexistence between two rival communities, had rushed home to write articles under headlines such as “Peace is still possible in Lebanon”, illustrated with big pictures of hte local priest and the Druze sheikh shaking hands and smiling.”

The journalists wrote their articles on 7 March 1977. On 16 March, following the death of Kemal Jumblatt, Druze armed men opened fire on Christian houses in Maasir al Chouf. …

In this conference for reconciliation, designed to encourage the relocation of the Christian refugees in their village of Maasir, the victims of the violence made a statement: ‘We buried our dead with dignity, we transcended our wounds and we forgave … The state wants time to work towards a solution: time would weakend resentment, and the effect of forgetting would be that the demands for justice would recede. We, the victims , are not asking for the impossible. but we refuse to be ignored, neglected and subjected to a fait accompli. We insist on our right to return to our village and our land. … at the same time, we believe in the logic of coexistence.'”

And here it was: the echo of Bosnia’s displaced, one decade ago, asking to return to their homes in Central Bosnia, in Herzegovina, in Republika Srpska. The universal dilemma of forgiveness after conflict, of the struggle for justice, while trying to build a viable future at the same time.

Leaving Beirut this Sunday morning, I felt that I would soon be back.

And that, in fact, we have all been here before.