There was a time not long ago when pro-globalization authors argued that the forces of international economic integration would soon make national boundaries redundant. Recently, others have suggested the opposite: that globalization is making national boundaries, at least those between rich and poor societies, all the more impenetrable. In fact, reality is more complex and more interesting than any of the latest grand theories would suggest. When it comes to policing their borders, rich societies face real choices; these choices can produce very different outcomes. Comparing the choices made in recent years by the member states of the EU with those made by the US has been the topic of a seminar held this week at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. The seminar, co-organised by ESI, featured Europeans, Americans and Mexicans, lecturers on Mexican politics at Harvard, experts in border management and technologies, columnists, officials working for Mexican institutions, and private sector representatives. Our opening question was: can anything be learned from comparing the EU and the US approaches to border management? Our hypothesis, based on our work in Southeast and Eastern Europe, is that there is plenty that the EU and the US can learn from each other.  Let me start with the conventional wisdom embraced by many of those who study trends along the US-Mexican border since the early 1990s. In a world without strong boundaries, migration pressures cannot be contained, the argument goes. In response to illegal migration pressures and the threat of organised crime, the militarisation of boundaries between rich and poor countries becomes the natural political response to popular feelings of insecurity. As Joseph Nevi writes in Operation Gatekeeper – The Rise of the “Illegal Alien” and the Making of the US-Mexico Boundary,

Let me start with the conventional wisdom embraced by many of those who study trends along the US-Mexican border since the early 1990s. In a world without strong boundaries, migration pressures cannot be contained, the argument goes. In response to illegal migration pressures and the threat of organised crime, the militarisation of boundaries between rich and poor countries becomes the natural political response to popular feelings of insecurity. As Joseph Nevi writes in Operation Gatekeeper – The Rise of the “Illegal Alien” and the Making of the US-Mexico Boundary,

“Intensified policing efforts are taking place along a variety of international boundaries between South Africa and Mozambique, Spain (Ceuta and Melilla) and Morocco, and Germany and Poland. Such efforts are parts of a war of sorts by relatively wealthy countries against ‘illegal’ or unauthorized immigrants. Yet at the same time, these same countries are increasingly opening their boundaries to the flows of capital, finance, manufactured goods and services.”

This is only an apparent contradiction, Nevin argues. It is natural that rich states seek to increase the benefits and limit the costs of transnational integration. This then leads to the creation of fortresses (‘Fortress America’ or ‘Fortress Europe’) and ‘gated communities’ of wealthy societies. A good illustration of this trend is, of course, the increase in the number of border agents in the US, which has gone from 450 in 1925 to 1,110 in 1950, 1,803 in 1975 and 9,212 in 2000 (Operation Gatekeeper, p. 197). Edward Schumacher Matos estimates that today it is close to 20,000. What these numbers show is that the effort to control the southern boundary of the US is a relatively recent phenomenon. One hundred years ago there was no serious concern about unauthorized entry across the US-Mexican border. Along the Arizona-Mexico border in 1900, one expert notes, “there was no need for coyotes, guides to sneak illegals through the border; there was no border markings (save a few stone pillars here and there), no immigration control and thus no illegals.” (OG, p.26) Today, the situation has changed considerably. The stretch of boundary between San Diego and Tijuana, writes Nevins, “is perhaps the world’s most policed international divide between two nonbelligerent countries.” For unauthorized migrants, the US-Mexican border is harder to cross now than at any point in history. At the same time, trade between the US and Mexico has grown sharply. Increasing commerce and more militarised boundaries – in an age of global insecurity, claims Nevins, such is the global trend. Except, of course, that this is not the case. Not only is there no militarised border between Germany and Poland; today, there is no physical boundary at all. When Poland joined the EU’s Schengen zone in 2007, border installations were dismantled. When Romania joins Schengen sometime in 2011, Germany’s external boundary will de facto shift from Poland’s Eastern border to the Prut River between Romania and Moldova. (To be admitted into Schengen, Romania has had to make significant investments in its ability to control its Eastern boundary.) Having crossed the Prut, you will be able to travel all the way to Gibraltar in southern Spain. One of the most interesting trends in the past year has been the acceleration of reforms in small and poor Moldova (the poorest country in Europe), carried out in response to a European promise of increasing freedom of movement for Moldovan passport holders. The promise is simple, and it has been made to other countries before: if Moldova carries out reforms that enhance the ability of Moldovan institutions (police, border guard, the ministries of justice and interior) to partner with EU institutions in fighting common threats, the EU will lift its visa requirements. Turn yourself into a partner, the logic goes, and your citizens can travel to the EU much more easily. It is important to underline that every one of these steps has been controversial, debated, and held up by concerns about security (this includes the next big step, the expansion of the Schengen area to Romania and Bulgaria, currently put into question by France). Likewise, the debate on visa free travel for Turkish citizens promises to be intense. At every stage, Europe’s border revolution has been contested; and at no stage can further progress simply be taken for granted. However, those who focus on the political debate of the moment would do well to look at the trajectory of Europe’s border revolution. Very soon after Schengen was created by five European countries in 1985, concerns increased in France. The fact that the idea of a borderless EU core (which led to Schengen) had been a Franco-German brainchild did not stop France from delaying implementation of the Schengen convention for many years even after it officially entered into force in September 1993, with French leaders citing concerns about the security implications of letting people enter France from Belgium or the Netherlands as late as in 1996. The fact that Italy had been a founding member of the EU did not make it any easier for it to join Schengen: the process actually lasted for over a decade, from Italy’s application in 1987 to its eventual entry in 1997. It is also useful to reflect on what has happened in Albania in the past two decades. At our seminar at Harvard, I began my presentation with a video clip of Albania’s collapse into chaos in 1997:

Anarchy in 1997. © 2008 pre tv. All rights reserved.

Remember, I told participants, until recently Albania was known throughout Europe only for its total collapse in the 1990s, the illegal migration of hundreds of thousands of its people within a few years to neighbouring Italy and Greece, and the vast profits made by organised crime syndicates, which controlled the speedboats that crossed the Adriatic by night. Now, however, many Albanian smugglers are out of a job: at the end of 2010 Albanian citizens will have obtained the right to travel to the EU visa free.

To qualify, Albanians had to carry out far-reaching reforms, however. And which country threatened to vote against Albania receiving visa free travel at the very end? You might have guessed it: France. And yet, after registering its concerns, France went along in the end.

It is not only Albanians but also the citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina who will enjoy the right to visa free travel in coming days for the first time in almost two decades. Bosnia-Herzegovina? In the early 1990s Ed Vulliamy was a reporter there, covering the country’s collapse into war, and then writing up his experiences in Seasons in Hell. At the time, Bosnia was the scene of massive ethnic cleansing, genocidal violence and collapsing institutions, and Ed’s book captured the sheer horror of it in Central Bosnia:

“By the middle of the Saturday afternoon, more than 30,000 escapees from the bloody mayhem left behind in Jajce – and the pitiful ramshackle remnants of an army, some 7,000 soldiers -had crossed the new, retreated Bosnian front at Karaula and now jammed every square of Travnik … The soldiers wandered aimlessly among them and their beasts and wagons, as lost and destitute as the civilians. It was like some woeful landscape from Tolstoy, or a war from another time: the life of a country town and its surrounding villages uprooted and driven out by war, with all its flotsam and jetsam. And another 15,000 were still out there, trapped by gunfire on the front … “

Since then Bosniaks have returned in significant numbers to Jajce; Travnik has a multiethnic police; and Bosnia’s crises are political and non-violent. Bosnia’s crime rate is below that of the Baltic states (which joined the EU in 2004); its police forces work; and its citizens feel safe crossing the former frontlines. These lines – which many had expected in 1995 to harden into Cyprus-style militarised internal boundaries – have since become basically invisible to the traveller. A decade ago, Bosnia did not control its own boundaries. Since then it has received ample praise (including by the US State Department) for its record on fighting human trafficking.

Ed Vulliamy: from Bosnia to Amexica

I mention Ed Vulliamy not only because his book is a useful reminder how far Bosnia (and the Balkans) have come since the 1990s, but also because Ed has since moved to the US and written a book about a very different war. As he tells his readers in Amexica – War Along the Borderline (2010), “I have been a reporter on many battlefields, yet nowhere has violence been so strange and commanded such revulsion and compulsion as it does along the borderline.” The borderline Ed writes about is that between the US and Mexico; the war he refers to is the “narco war” wreaking havoc on communities from the Pacific to the Gulf of Mexico.

While Europe has dismantled and made more porous thousands of kilometres of borders (by taking apart the Iron Curtain and the Berlin Wall, abolishing border controls within the Schengen system, lifting visa requirements for Central Europeans, extending Schengen to the East, and, most recently, lifting visa requirements for the Balkans), the US has done the opposite. As Ed writes,

“In 1994 the United States initiated Operation Gatekeeper in San Diego, Operation Hold the Line in El Paso, and another similar operation in the Rio Grande Valley. Since then … the border has become, and continues to become, a military front line, along which run more than six hundred miles of fence enhanced by guard posts, searchlights, and heavily armed patrols. In places where there is no fence, there are infrared cameras, sensors, National Guard soldiers and SWAT teams from other, specialist law enforcement columns, like the Drug Enforcement Administration … from the other side, apart from the tidal wave of drugs and migrants smuggled across the border, there are the killings …”

Vulliamy takes his readers to Ciudad Juarez, “the world’s most murderous city”, on the Mexican side of the border opposite El Paso. Juarez saw 2,657 people killed in 2009 (the total number of people killed in Mexico since President Calderon launched a military offensive against the drug cartels in December 2006 has now exceeded 23,000).

Vulliamy notes that one in five Mexicans either visits, or works in, the US at one time in his life. He describes the economy that has developed around the narco-trade and the gun shows in Arizona and Texas. He estimates that there are more than 6,700 arms dealers within a half day’s drive from the border in the US (three dealers per mile of frontier) and that between 90-95 percent of weapons seized in Mexico’s narco war originate from the US. As a June 2009 report by the US Government Accountability Office notes, although the violence in Mexico “has raised concern, there has not been a coordinated US government effort to combat the illicit arms trafficking to Mexico that US and Mexican government officials agree is fueling much of the drug-related violence.” Ed also writes about the paradoxical effect of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which has seen business ties increase and the border harden.

Death in North America

Not long ago every book or article about the Balkans started with references to killings and cults of irrational violence. The same is true today in descriptions of the US-Mexican border. One book Operation Gatekeeper starts with a description of the owner of a gas station/cafe in Ocotilio Wells, 90 miles east of San Diego in California:

“On one bulletin board he had tacked up photographs of seven or eight cadavers: all of them young Mexican men he had discovered in the arroyos between Ocotillo Wells and the nearby Border. … “They was all shot. In the back.”

Another book by John Annerino, Dead in their Tracks – Crossing America’s Desert Borderlands in the New Era (2009) includes a “comprehensive border death toll” (2003: 336 people died trying to cross the US-Mexico border; 2004: 214; 2005: 241; … 2007: 237). It opens with a glossary of key terms for the border:

“I have used the terms bajadores (bandits, take-down crews or kidnappers), bandidos (border bandits), burreros(drug mules), caza-migrantes (migrant hunters), contrabandistas (smugglers), coyotes (people smugglers), narcotraficantes (drug traffickers), pistoleros (gunmen), polleros (“chicken dealers” or people smugglers) and raiteros (drivers who shuttle imigrants from pickup points).”

Annerino also points out just how lucrative smuggling people across the border has become, describing the scene in the Mexican border town of Altar:

“This afternoon I count roughly 500 people walking the streets and church plaza, so I start running the numbers … If the crossing fee is closer to $ 2,500 per person, or the coyote increases the $ 1,500 fee to $ 2,500 or more during the border crossing which I am told is common, get out your calculator and do the new border math. A recent Associated Press report put Arizona’s human smuggling revenues at $ 2.5 billion a year.”

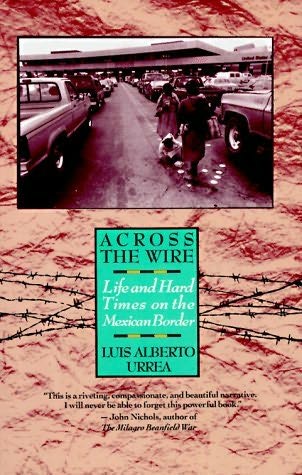

And as another author, Luis Alberto Urrea, describes in Across the Wire – Life and Hard Times on the Mexican Border, focusing on the Tijuana region, paying this amount does not guarantee safe passage:

“If the coyote does not turn on you suddenly with a gun and take everything from you himself, you might still be attacked by the rateros. If the rateros don’t get you, there are roving zombies that can smell you from fifty yards downwind – these are the junkies who hunt in shambling packs. If the junkies somehow miss you there are the pandilleros – gang-bangers from either side of the border who are looking for some bloody fun. They adore “tacking off” illegals because it is the perfect crime: there is no way they can ever be caught”

Now, beyond the sheer human tragedy in all these descriptions, there is a poignant policy question raised by all these accounts: is this border regime, are these changes – the militarisation that has taken place in recent decades – actually in the interests of those in the US who are concerned about security? Just take a look at a recent article in the New York Times from summer 2010 for another horrific description of trends along the border (The Mexican Border’s Lost World):

“Never a particularly pretty place, the border is at its ugliest right now, with violence, tensions and temperatures all… on high. Once thought of by Americans as just a naughty playland, the divide between the United States and Mexico is now most associated with the awful things that happen here. In towns from the Pacific to the Gulf of Mexico, drug gangs brutalize each other, tourists risk getting caught in the cross-fire, and Mexican laborers crossing the desert northward brave both the bullets and the heat. Last week, a federal judge in Arizona blocked portions of new far-reaching immigration restrictions that she said went way too far in ousting Mexicans. Meanwhile, National Guard troops are preparing to fill in as border sentries. All these developments are unfolding in what used to be a meeting place between two countries, a zone of escape where cultures merged, albeit often amid copious amounts of tequila. The potential casualties at the border now include a way of life, generations old, well-documented but decaying by the day.”

After all, European citizens are as concerned about illegal migrants as those in the US. There are right wing parties in many European countries. The amount of illegal drugs entering the EU is comparable (in fact, according to UN figures, even higher) to those that enter the US.

And yet, in a process driven by interior ministers and focused on increasing security, the EU’s response to concerns about events on the other side of its Eastern border has been very different from that pursued by their US counterparts. This has been the European border revolution of the past three decades, which ESI has set out to analyse and understand.

This was not a project of humanitarians … it was a conscious decision that new thinking was required to ensure security in an age of globalisation. It was a process controlled by interior ministers, in which critical questions were asked at every stage. As French Foreign Minister, Herve de Charette, put it in September 1995, explaining France’s unwillingness to lift its controls at the Belgian (!) frontier:

“If it seems, as it is the case, that our citizens’ security depends also on the border controls, it is understood that we have to keep them.”

In the end, however, the dramatic transformation of Europe’s border regimes continued.

Is any of it relevant to debates in North America? Certainly the consensus at the Harvard seminar was that it is worth exploring in more depth. At the very least it suggests that even under conditions of globalisation policy makers have choices – and that there is more than one way in which to think about creating secure borders.

PS: Next steps forward

The Harvard seminar turned into a very informative meeting, and out of it emerged an agenda for further steps.

First, it is necessary to establish a network of scholars and policymakers in the US and in Mexico who had worked on the border issues, including those who had done any comparative work. (If you read this and if you are interested in becoming part of such a network please write to mary_hilderbrand@harvard.edu and Gerald_Knaus@hks.harvard.edu)

Alexander Schellong, Rodrigo Garza Zorrilla, Edward Schumacher-Matos, Mary Hilderbrand, Omar del Valle Colosio, Philipp Mueller, Gerald Knaus, Pedro Lichtle, Jose Luis Mendez, Javier Lichtle, Adriana Villasenor

Second, there is a need to present the complex politics and security logic behind the recent EU border revolution; this was not after all a humanitarian transformation, nor was it at any moment easy. In fact, the revolution is far from over, as the dramatic events in recent months along the Greek-Turkish border have made clear (not to mention the EU’s Southern border). How will the EU respond to the challenge of Turkey when it comes to freedom of movement and travel?

Third, there is a need to better understand the US policy process, the politics as well as the technocratic arguments which most shape the debate.

Fourth and most importantly there is a need to understand how the current status quo along the US-Mexican border is working and how it is failing; and for whom it is working and who is losing.

Particularly the comparison in relations between the US and Mexico and the EU and Turkey promises to be revealing in what it tells us about US and European soft power, about the choices facing rich countries and about the politics behind border management. For more, watch this space; and stay tuned to the ESI “Border Revolution website”.

A few facts as background to inform a serious debate on comparative border experiences. Look at GDP per capita (in PPP) in 2009 according to the IMF. On the one side of the border wealthy countries:

USA (46,000 USD per capita)

Germany (34,000 USD per capita)

On the other side poorer countries:

Poland (18,000 USD pc), which has joined the EU in 2004

Mexico (14,000 USD pc)

Turkey (12,000 USD pc)

Romania (12,000 USD pc), which has joined the EU in 2007

Albania (7,000) USD pc), which has visa free travel since end 2010

As for the relative size of the populations concerned:

USA: 311 million vs. Mexico: 112 million

EU 15: 398 million

EU 27: 500 million

Poland: 38 million (visa free access since the early 1990s)

Eastern Balkans (Romania/Bulgaria): 30 million (members of the EU since 2007)

Western Balkans: 25 million (visa free travel since late 2009 and 2010)

Turkey: 73 million

On 14 June 1985, the Schengen Agreement on the gradual abolition of checks at the common borders between Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, was signed on board the cruise ship ‘Princesse Marie-Astrid’, moored at Schengen, Luxembourg. Photo: plaza.lu

On 14 June 1985, the Schengen Agreement on the gradual abolition of checks at the common borders between Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, was signed on board the cruise ship ‘Princesse Marie-Astrid’, moored at Schengen, Luxembourg. Photo: plaza.lu The Danish border with Germany

The Danish border with Germany