This is a translation of the action plan “Westlicher Balkan und EU-Nachbarschaft” I wrote for the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP). It was part of the DGAP project “Action Plans Structures German Foreign Policy,” a ten-month process of reflection and strategy resulting in ten concrete action plans.

Of those I contributed two (English translations will be available in November):

- Aktionsplan Westlicher Balkan und EU-Nachbarschaft – Wie Deutschland zu dauerhaftem Frieden auf dem Balkan beitragen kann

- Aktionsplan Migration und Außenpolitik – Wie Deutschland die irreguläre Migration begrenzen und Flüchtlingen helfen kann

Nemačko Društvo za Spoljnu Politiku (DGAP)

Akcioni plan Zapadni Balkan i EU-Susedstvo

Kako Nemačka može da doprinese trajnom miru na Balkanu

Više od dve decenije nemačka spoljna politika posvećena je sprečavanju obnove tenzija, unutrašnjo-političkih ili čak oružanih sukoba na Zapadnom Balkanu. Da je ovo uspelo od 1999. godine takođe je uspeh nemačke politike.

20.09.2021

Poslednjih godina se povećao rizik od neuspeha stabilizacione politike EU i Nemačke na Balkanu. U Srbiji, najmoćnijoj zemlji u regionu, vodeći članovi vlade ponovo otvoreno govore o mogućim oružanim sukobima i dovode u pitanje granice na Zapadnom Balkanu. Osuda bivšeg generala Ratka Mladića za genocid u Srebrenici, u proljeće 2021. dovela je do ekstremno nacionalističkih reakcija vlasti i medija bliskih vladi. Godinama rastući izdaci za vojnu potrošnju takođe jasno stavljaju do znanja da bi destabilizirajuća politika prema susednim državama, poput Bosne i Hercegovine i Kosova, bila ne samo zamisliva, već čak i verovatna da nema stabilizacijske kontra-strategije Nemačke i njenih saveznika.

Kosovski sukob tek što je bio okončan kada su u julu 1999. godine nemački kancelar Gerhard Schröder, američki predsednik Bill Clinton i šefovi vlada svih članica EU došli na veliki balkanski samit u Sarajevu. Na Kosovu, u četvrtom balkanskom ratu za manje od jedne decenije, skoro milion Albanaca je bilo proterano u susedne zemlje. Političare, koji su se tada sastali u Sarajevu, spajalo je gnušanje prema nacionalizmu, koji je u kratkom vremenskom periodu koštao toliko života. Oni su se obavezali da će „sarađivati na očuvanju multinacionalne i multietničke raznolikosti zemalja u regionu i u zaštiti manjina“. Svečano su izjavili: „Zajedno ćemo raditi na integraciji Jugoistočne Evrope u kontinent na kojem granice ostaju nepovredive, ali više ne znače podelu te nude mogućnost kontakta i saradnje.“ Obećali su evropski mir, postmoderni “Pax Europeana”. Nemačka je imala vodeću ulogu u formulisanju ovog cilja.

Dve decenije mira

Dok su u drugoj polovini devedesetih pre svega USA imale vodeću ulogu u stabilizaciji regiona -nakon završetka ratova u Bosni (1995.) i na Kosovu (1999.)- to se promenilo od 2000. nadalje. EU je postala vodeća igrač, a unutar EU je Nemačka igrala glavnu ulogu: sa sve većim uticajem. Zapadni Balkan je tako postao prvi i do danas najuspešniji test zajedničke evropske spoljne politike, pri čemu je EU i njenim državama članicama uspelo geopolitičko čudo demokratske stabilizacije.

Crna Gora je svoju nezavisnost postigla mirnim putem, uz podršku široke multietničke koalicije. Danas u bosanskoj “Republici Srpskoj” ponovo živi više od 220.000 Ne-Srba, proteranih sa srbske teritorije tokom rata 1992-1995. Severna Makedonija ima osnovne škole na četiri jezika, a albanski je službeni jezik u celoj zemlji. Većina kosovskih Srba koji su živeli na Kosovu pre 1999. godine ostali su tamo i posle 1999. godine. Srpski je službeni jezik na Kosovu. U celom regionu vlada mir već dve decenije.

Poslednjih nekoliko godina oko EU vidimo ratove i izbijanja nasilja: u Gruziji, Iraku, Siriji, Ukrajini, Libiji i na Kavkazu. U mnogim istočnoevropskim državama, članicama Saveta Evrope, sada ponovo ima političkih zatvorenika. Zapadni Balkan je, s druge strane, ostao miran. Danas nema političkih zatvorenika ili sistematskih kršenja ljudskih prava ni u jednoj zemlji u regionu. Nemačka je povukla svoje vojnike iz Bosne i Hercegovine, ne brinući da bi zbog toga moglo doći do izbijanja novih borbi. Samo na Kosovu je trenutno stacioniran mali kontingent od oko 80 vojnika nemačkog Bundeswehra.

Zastoj

Ne samo na Zapadnom Balkanu već i u evropskom susedstvu uticaj Nemačke na unutrašnjo- i spoljnopolitičke razvoje više od dve decenije je tesno povezan sa verodostojnošću evropske integracione perspektive. Tamo gde ona postoji, Nemačka ima veliki uticaj, bilateralno i preko Evropske Unije, te može da realizuje svoje interese. Izručenje traženih ratnih zločinaca koje traži Njemačka, modalitet za referendum o nezavisnosti Crne Gore, prvi koraci u procesu normalizacije između Srbije i Kosova, kompromis sa Grčkom oko imena države Severna Makedonija, dalekosežne pravosudne reforme u Albaniji i druge teške odluke su sprovedene u regionu, jer su elite smatrale da je to neophodno kako bi se napredovalo ka evropskim integracijama: koje su želele i smatrale realnim.

Tamo gde ta „evropska perspektiva“ nestaje, reducira se brzo i nemački uticaj u regionu. Razvoj odnosa Turske i EU jasno je upozorenje šta se u bliskoj budućnosti može desiti i na Zapadnom Balkanu. U Turskoj je postojao period rastućeg uticaja Nemačke i EU posle 2000. Ali onda su pregovori o pristupanju EU sa Turskom iz različitih razloga izgubili svaki kredibilitet i na kraju su zamrznuti. U isto vreme rasle su napetosti između Turske s jedne strane i Nemačke i drugih zemalja EU s druge – sve do vojnih pretnji Ankare Grčkoj i Kipru. Nemačka i EU su se pokazele nemoćnima glede demontaže turske pravne države i kršenja osnovnih ljudskih prava.

Sada i na Zapadnom Balkanu perspektiva integracije -koja je bila toliko moćna pre nekoliko godina- gubi kredibilnost za političke elite i društva. U važnim državama članicama EU, poput Francuske ali i Holandije, postoji veliki skepticizam u pogledu bilo kakve dalje runde proširenja. Stoga je novo učlanjenje u EU postalo malo verovatno a proces proširenja već godinama u zastoju. Trenutno su samo dve od šest zemalja u regionu stvarno uključene u pregovore o pristupanju: Srbija i Crna Gora. Međutim, pregovori ove dve države o pristupanju -i reforme u njima- se ne pomeraju sa mesta već godinama. Albanija i Severna Makedonija godinama čekaju na početak pregovora. Bosna i Hercegovina nije čak ni zvanični kandidat za članstvo. Neke zemlje članice EU ne priznaju Kosovo kao nezavisnu državu i stoga se Kosovo ne može ni kandidovati za pridruživanje EU.

Uloga Nemačke

U decembru 2003. EU je usvojila prvu evropsku bezbednosnu strategiju koja je sadržala upozorenje: „Izbijanje sukoba na Balkanu nas je podsetilo da rat nije nestao sa našeg kontinenta.“ EU je povezala budućnost vanjske politike EU sa sopstvenim uspehom u Jugoistočnoj Evropi: „Kredibilitet naše spoljne politike zavisi od učvršćivanja naših tamošnjih postignuća.”

To i dalje važi. Od Beograda do Tirane, od Sarajeva do Prištine, Njemačka je danas najpriznatiji i najvažniji evropski partner. Realno: Zapadni Balkan bi u narednih pet godina mogao postati spoljnopolitička priča o uspehu Nemačke i EU ako bi se perspektiva integracije ponovo učinila verodostojnom. Tada bi bilo moguće upotrebiti mudru diplomatiju kako bi se otvorena spoljnopolitička pitanja približila finalnom rešavanju: od dijaloga između Srbije i Kosova do trajne stabilizacije multietničkih demokratija u Severnoj Makedoniji, Bosni i Hercegovini i Crnoj Gori. U regionu u kojem se sve države orijentišu prema EU, njenim standardima i vrednostima, ali i njenim pravilima i institucijama, pitanja statusa bi takođe bila rešiva.

I naredna nemačka vlada takođe ima veliki interes za stabilnost u regionu koji je, sa četiri rata i genocidom, svojevremeno bio najkrvaviji konfliktni region na svetu a devedesetih godina prošlog veka prouzrokovao veliki pokret izbeglica. Da bi se eliminisao rizik povratka u nestabilnost nije dovoljno pustiti da se trenutni proces nastavi. Potrebna je nemačka inicijativa.

Preporuke za obnovljenu nemačku Zapadnobalkansku Politiku

Poslednjih godina vlade u Beogradu, Podgorici, Prištini, Sarajevu, Skoplju i Tirani ispunile su mnoge zahteve Nemačke i EU te poboljšale odnose između etničkih grupa i sa svojim susedima. Političari u Crnoj Gori (pre i neposredno nakon početka pristupnih pregovora 2012.), Srbije (između 2010. i 2014.), Severne Makedonije (2004.-2005., kad se zemlja nadala statusu kandidata te ponovo između 2017. i danas) te Albanije iznova i iznova su sprovodili politički zahtevne reforme, imajući na umu konkretan i atraktivan cilj. Danas u regionu nedostaju slični mobilizirajući ciljevi. U nemačkom je interesu da se to promeni. Ali to može uspeti samo ako Berlin ozbiljno shvati zabrinutost svojih partnera u EU.

Inicijativa Nemačke trebalo bi da se zasniva na predlogu koji je Francuska predstavila krajem 2019. godine, a koji predviđa različite faze integracije balkanskih zemalja. Ova ideja se može pojednostaviti kako bi bila kredibilna u EU a istovremeno definisala atraktivan cilj za elite regiona u narednih nekoliko godina. Ovako bi to moglo da funkcioniše:

1) Predlaže se pristupni proces u dve faze. Cilj pregovora sa svih šest država u regionu ostaje punopravno pridruživanje, ali se nudi novi i konkretan posredni cilj: potpuni pristup evropskom unutrašnjem tržištu.

2) U prvoj fazi, svaka država u regionu koja ispunjava neophodne uslove trebalo bi da pristupi unutrašnjem tržištu, poput Finske, Švedske i Austrije 1994. Ostvarivanje ovog pristupa do 2030. bio bi realan cilj za sve zemlje na Zapadnom Balkanu. Oni bi uživali u četiri slobode – slobodnom kretanju robe, kapitala, usluga i radne snage – baš kao što to rade Norveška i Island danas. U tom cilju, EU bi trebala stvoriti okvir Ekonomskog Prostora Jugoistočne Evrope (EPJE). Nemačke institucije: Ured Saveznog Kancelara, MIP i druga ministarstva izradili bi poseban predlog i založili se za njega u EU.

3) Jačanje vladavine prava u regionu pri tome ostaje centralna komponenta procesa integracija, jer svi uslovi za vezani za demokratiju, vladavinu prava i ljudska prava moraju biti u potpunosti ispunjeni da bi se zemlja mogla pridružiti unutrašnjem tržištu i Ekonomskom Prostoru Jugoistočne Evrope. Sledeća nemačka savezna vlada trebalo bi da se založi za proširenje redovnih izveštaja o vladavini prava u EU na zemlje Zapadnog Balkana.

4) Istovremeno, Nemačka bi trebalo da se založi i za jačanje Saveta Evrope – kojem pripada pet od šest zemalja u regionu – i da promoviše brzi prijem Kosova u njega. Važno je da implementacija presuda Evropskog Suda za Ljudska Prava u čitavom regionu postane centralni uslov za integraciju u EU.

5) U tu svrhu, EU bi trebala još pomnije da prati važne sudske procese u svih šest zemalja kako bi mogla utvrditi da li pravosuđe radi nezavisno. Evropska Komisija treba da izradi detaljne izveštaje o korupciji za Zapadni Balkan, koristeći istu metodologiju koja se koristila za izveštaje o korupciji u državama članicama EU 2014. godine. Novi izveštaj svake dve godine mogao bi osigurati uporedivost među zemljama.

6) U tom kontekstu bi približavanje i normalizacija odnosa između Kosova i Srbije već u naredne četiri godine bilo realna. Usvajanjem istih pravila EU, državne granice bi postale manje važne. Pre nego što se pridruži zajedničkom tržištu, Srbija bi takođe morala da prihvati sadašnje granice Kosova. Opšti cilj bi bio da granice između balkanskih zemalja budu isto tako nevidive, kao što je danas norveško-švedska granica.

Pristupanje unutrašnjem tržištu EU, u okviru EEA EU-a i Zapadnog Balkana do 2030., ambiciozan je ali ostvariv cilj za sve zemlje Zapadnog Balkana. Realna perspektiva uživanja četiri slobode – za robu, kapital, usluge i rad (sa prelaznim periodima, kad EU smatra da je to neophodno) – u roku od nekoliko godina mobiliziralo bi društvo u celini te stvorio novu ekonomsku dinamiku.

Cilj je region, koji je ekonomski tako blisko povezan sa EU kao Norveška i Island danas. Jaz u blagostanju sa ostatkom Evrope trebalo bi brzo da se smanji, baš kao što su Rumunija ili baltičke zemlje to tako spektakularno postigle od 2000. Vladavinu prava i zaštitu manjina treba ojačati. Slično unutrašnjim granicama EU u šengenskom sistemu, granice između balkanskih zemalja takođe bi trebale postati nevidive, kako bi se ublažio politički spor oko njih.

Ovaj cilj se može postići bez previše napora i bez rizika za Nemačku i EU. To bi bio nemački i evropski spoljnopolitički uspeh. I to bi bio signal drugim zemljama u susedstvu da se dobri odnosi i posvećenost funkcionalnoj integraciji sa EU politički isplate i bivaju realnost.

Višestruki interesi Nemačke u regionu još uvek se najbolje mogu realizovati u okviru koherentne politike EU prema Balkanu. U poslednje dve decenije, moć Nemačke na Zapadnom Balkanu zasnovana je prvenstveno na realističnoj utopiji: verodostojnom obećanju bolje budućnosti kroz integraciju u stabilnu i prosperitetnu EU, koja omogućava sličan mir na Zapadnom Balkanu kakav je proteklih decenija u EU postojao: „Bezbednost kroz transparentnost i transparentnost kroz međuzavisnost.“

Ovaj „postmoderni mir“ u EU, koji je opisao Robert Cooper, učinio je vekovnu politiku alijansi i balansiranja moći suvišnom. Članice EU, rekao je Cooper, ne razmišljaju o tome da naprave invazije jedna na drugu. Izazov na Zapadnom Balkanu je postizanje sličnog trajnog mira u kom granice gube na značaju, vojske više ne služe za zastrašivanje, a manjine žive sigurno.

Oružani sukob bio bi onda nezamisliv na Zapadnom Balkanu kao što je to danas među članicama Evropske Unije. Ako sledeća nemačka savezna vlada može pomoći u implementaciji takve “Pax Europeana” na Zapadnom Balkanu, ona će nastaviti nemačku i evropsku priču o uspehu, priču u kojoj se mir obezbeđuje integracijom i umrežavanjem.

A Balkan, od bureta baruta postaje region stabilnosti za narednu generaciju.

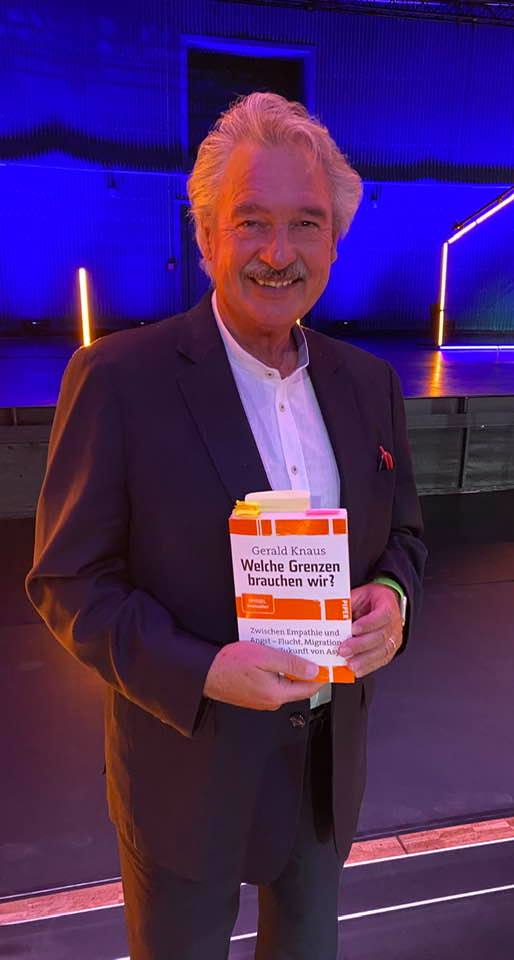

Autor: Gerald Knaus, predsednik European Stability Initiative (ESI)

Prevod: Mirko Vuletić